What Is Second Victim Syndrome? A Comprehensive Guide for Healthcare Professionals

- Patricia Maris

- 11 hours ago

- 20 min read

Ever walked out of a surgery feeling like you'd just lost a patient, even though everything went technically right? That knot in your chest is something many of us in the front‑line health world know far too well.

We call that feeling the "second victim" effect – a cascade of self‑doubt, anxiety and guilt that hits clinicians after a medical error or a near‑miss. In plain language, it's the emotional fallout that hits the health‑care professional, not the patient. If you're a nurse pulling a 12‑hour night shift, a resident scrambling through a hectic ER, or a seasoned surgeon reviewing a tricky case, you’ve probably sensed it.

So, what exactly is second victim syndrome? At its core, it's a recognised stress response that can lead to sleepless nights, impaired decision‑making, and even burnout if left unchecked. Studies show that up to 40 % of physicians report feeling like a second victim at least once in their career. That number climbs higher among nurses and allied health staff, who often juggle staffing shortages and high‑stakes decisions.

Imagine you just administered the wrong medication dose. The patient is fine after a quick correction, but the replay in your mind keeps looping. You start questioning every future prescription, your confidence erodes, and you might avoid certain procedures altogether. That's the syndrome in action, and it’s not a sign of weakness – it’s a signal that your wellbeing needs attention.

Recognising the signs early can make all the difference. Look for red flags like persistent rumination, feeling detached from your work, or physical symptoms such as headaches and stomach upset after a stressful event. When these pop up, treating them like any other clinical symptom – by assessing, diagnosing, and intervening – is essential.

One practical step you can take right now is to jot down the incident in a confidential wellbeing self‑assessment. Our platform helps you map those emotional spikes to a personalised Wellbeing Profile, giving you data‑driven insights on where to focus your resilience building. It’s a simple habit: after a tough case, spend five minutes noting what happened, how you felt, and one small action you could try next time.

Another tip is to reach out to a trusted colleague or a peer‑support program within your organisation. Sharing the story often reduces the emotional load dramatically – you’re not alone, and the collective wisdom can turn a painful episode into a learning moment.

If you want a deeper dive into the definition and origins of the term, check out our detailed guide on what is Second Victim Syndrome? It walks you through the history, key research findings, and why it matters for every health‑care professional today.

Bottom line: the second victim experience is common, but manageable. By acknowledging it, tracking it, and leaning on evidence‑based resources, you can protect your mental health and keep delivering the care you love.

TL;DR

If you’ve ever felt a knot in your chest after a tough case, you’re experiencing what is second victim syndrome—a common, stress‑response that can erode confidence and increase burnout risk.

A self‑assessment, peer support, and tools like e7D‑Wellness’s Wellbeing Profile help you recognise triggers, track emotions, and start rebuilding resilience.

Step 1: Recognize the Emotional Impact

Ever walked out of a tricky case and felt that hollow thud in your chest? That little knot isn’t just fatigue – it’s the emotional echo of second‑victim syndrome showing up. The first thing we need to do is name the feeling, because unnamed pain tends to linger like a bad after‑taste.

Start by doing a quick mental scan. Ask yourself:Did I replay the moment over and over?Am I noticing a sudden headache, stomach churn, or a sudden urge to avoid similar cases?Those physical cues are your body’s alarm system, flashing red lights that something’s off.

Here’s a simple three‑question check‑in you can run in under a minute after a shift:

What exactly happened? (Keep it factual, no judgment.)

How did it make me feel in the moment? (Name the emotion – anxiety, guilt, shame, frustration.)

What’s the physical reaction right now? (Heart rate, tension, nausea?)

Write those answers down in a notebook or, better yet, in our confidential self‑assessment tool. The act of externalising the experience helps break the loop of rumination.

Now, let’s talk about patterns. If you notice the same scenario triggering the same emotional storm week after week, you’re probably dealing with a deeper habit, not a one‑off glitch. That’s where the Symptoms and Signs of Second Victim Syndrome page can help you map the red flags to a bigger picture.

So, what should you do when the check‑in reveals a strong reaction? First, give yourself permission to feel it. It’s okay to say, “I’m shaken,” without trying to immediately fix it. That acceptance creates a tiny gap where you can choose a healthier response.

Second, reach for a quick grounding technique – a 30‑second breath count, a sip of water, or a brief stretch. It’s not a cure, but it nudges your nervous system off the fight‑or‑flight edge.

Third, consider the environment that contributed to the stress. Was the electronic health record glitchy? Were you covering extra patients because staffing was thin? Those operational factors are often the hidden culprits behind emotional overload.

Speaking of operational factors, many clinicians find that improving the tech backbone of their workplace can actually reduce the frequency of these high‑stress moments. Managed IT services for healthcare can streamline workflows, keep patient data secure, and free up mental bandwidth, which indirectly cushions you against the emotional fallout of a near‑miss.

And don’t forget the body‑mind connection. Physical resilience feeds emotional resilience. A partner like XLR8well offers proactive health programmes that complement the mental‑wellness steps you’re taking, from nutrition tweaks to movement breaks tailored for busy clinicians.

Here’s a quick habit you can adopt right now: after each shift, set a timer for five minutes and jot down the three‑question check‑in. Over a week, you’ll start seeing trends – maybe it’s a particular type of case, a certain time of day, or even a specific equipment issue. Those trends become the data you need to talk to a supervisor or to tweak your own workflow.

Want to see this in action? Below is a short video that walks through a real‑world example of a clinician using the check‑in method right after a demanding ER night.

Take a breath, let that video settle, and then consider how you might adapt the technique to your own routine. The goal isn’t perfection; it’s awareness.

Step 2: Assess Organizational Support Systems

Okay, you’ve spotted the emotional knock‑back. Now ask yourself: does my workplace actually have anything in place to catch that fall? If you’re scrolling through endless policy PDFs and still feel alone, you’re probably missing a key piece of the puzzle – the organisational safety net.

First, take a quick inventory of formal programmes. Do you have a dedicated second‑victim support line? A peer‑debrief session after a critical incident? A clear, written policy that says “yes, it’s okay to feel upset and we’ll help you”? If the answer is “no” or “I’m not sure,” you’ve identified a gap you can start to close.

Map the existing resources

Grab a notebook (or open your e7D‑Wellness self‑assessment tool) and list every resource you can think of – from employee‑assistance‑program hotlines to informal coffee‑break chats with senior clinicians. For each item, note three things: who runs it, how you access it, and what the expected outcome is. This simple matrix turns vague ideas into concrete data you can discuss with leadership.

Pro tip: many hospitals already host a Second Victim Support Programs page on their intranet. If you can’t find it, ask your quality‑improvement office – they often know where the hidden resources live.

Ask the right questions

When you meet with a manager or a safety officer, bring a short list of focused questions. Examples:

What’s the protocol for a clinician who reports feeling like a “second victim” after a near‑miss?

Are there regular, protected time slots for peer debriefs?

How does the organisation track participation and outcomes?

These questions do two things: they show you’re proactive, and they surface any invisible barriers – like a policy that says you need a supervisor’s sign‑off before you can attend a support session.

Look for systemic safeguards

Beyond emotional support, assess the structural elements that can prevent the incident from happening again. Do you have a “just‑culture” approach that focuses on system‑level fixes rather than blame? Is there a regular morbidity‑and‑mortality (M&M) conference that invites frontline staff to speak without fear?

Data from the APhA’s consensus definition of second‑victim syndrome highlights that most adverse events stem from complex system flaws, not individual negligence. When organisations invest in root‑cause analysis tools, checklists, and simulation training, they indirectly lower the emotional toll on clinicians.

Take actionable steps

1.Document the gap.Write a one‑page brief summarising what you found – missing programmes, unclear policies, or absent metrics. Keep the tone collaborative: “We have an opportunity to strengthen our safety culture.”

2.Propose a pilot.Suggest a low‑effort initiative, like a 30‑minute peer‑support huddle after every high‑risk procedure. Offer to co‑lead it or to coordinate with the existing wellness team.

3.Set measurable targets.For example, “Increase second‑victim debrief participation from 0 % to 30 % within three months.” Numbers make the conversation concrete and help leadership see ROI.

4.Leverage e7D‑Wellness.Our platform can generate anonymised dashboards that show how many clinicians are logging stress spikes after specific events. Sharing these insights with administration can turn personal stories into organisational data.

5.Follow‑up.After a month, revisit the pilot’s results. Celebrate wins (even small ones) and tweak the process based on feedback.

Remember, assessing support systems isn’t a one‑off audit; it’s an ongoing conversation. The more you surface the reality of second‑victim experiences, the more likely your institution will allocate resources to protect its people.

So, what’s the next step for you? Grab that notebook, map the resources, and start a dialogue with your safety champion. The sooner you surface the gaps, the faster you can build a culture where clinicians feel seen, supported, and safe.

Step 3: Implement Immediate Coping Strategies

You've just mapped the emotional impact and scoped the organisational safety net. Now the question is: what can you do *right this minute* when the knot tightens after a tough case? The answer lives in a handful of bite‑size actions that you can slip into a busy shift without needing a whole new programme.

Pause and breathe

First, hit the pause button. It sounds almost too simple, but a deliberate three‑breath reset can drop the physiological stress surge by a noticeable margin. In practice, inhale for a count of four, hold two, exhale for six. Do it three times, eyes closed if you can. The rhythm sends a signal to the nervous system that the threat has passed, buying you a few seconds to think instead of react.

Ground yourself in the present

Next, bring your awareness back to the room. Name five things you can see, four you can hear, three you can touch, two you can smell, and one you can taste. This old‑school grounding trick pulls the mind out of the replay loop that often defines what is second victim syndrome. It feels a bit odd at first, but clinicians report it works like a mental “reset button.”

Micro‑debrief on the spot

Instead of waiting for a formal debrief, try a five‑minute micro‑debrief with a trusted colleague. Ask two quick questions: “What happened?” and “What’s one thing I can do differently next time?” Keep it factual, keep it short. Even a brief exchange can turn an internal monologue into shared language, which lessens the feeling of isolation.

Quick reset toolkit

Keep a small “reset kit” in your pocket or locker. It might include:

A lavender roll‑on or a scented wipe – scent can calm the amygdala.

A stretch band – a few seconds of gentle resistance work releases tension.

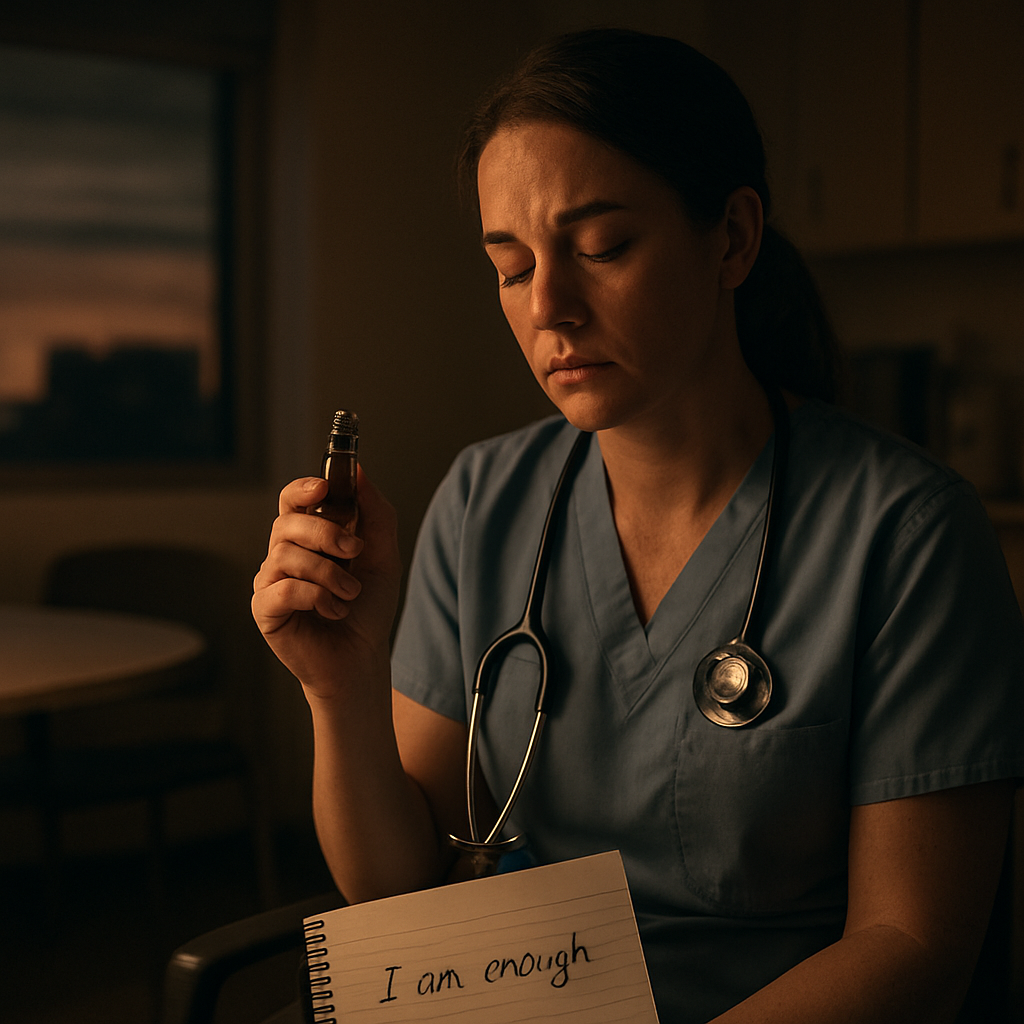

A notecard with a personal mantra, like “I did my best, I’ll learn.”

When the anxiety spikes, pull out one item and give yourself permission to pause. The ritual itself reminds your brain that you’re in control.

So, how does this look on a real shift? Imagine you’re an emergency nurse who just administered a medication dose that was later flagged as high‑risk. Your heart races, and you start replaying the event. You step into the supply closet, take three deep breaths, run through the five‑sense grounding, and jot a quick note on your notecard: “Medication error – alert pharmacy, review protocol.” You then catch a moment with a colleague, share the gist, and both agree to double‑check doses for the next hour. Within ten minutes, the pressure eases enough for you to continue caring for patients.

Leverage your Wellbeing Profile

Platforms like e7D‑Wellness make the “what’s next” step easier. After you’ve used the pause‑and‑breathe routine, log the moment in your confidential wellbeing self‑assessment. The system tags the entry with the coping technique you used, then suggests the next low‑effort strategy based on patterns it sees in your data. Over days, you’ll notice which tools cut your stress fastest and can build a personal “fast‑track” playbook.

Turn the moment into a habit

Finally, embed these actions into your routine. Set a reminder on your phone to do the three‑breath reset at the end of each shift, or keep a sticky note on your badge that reads “Breathe – Ground – Share.” The goal isn’t to eliminate stress – that would be unrealistic – but to create a reliable safety valve you can pull the moment you feel the knot tighten.

Give one of these strategies a try today. Notice how quickly the pressure loosens, and then keep a quick note of the result. Small, intentional steps add up, and before long you’ll have a personal toolbox that feels as essential as your stethoscope.

Step 4: Develop Long‑Term Resilience Plans

Okay, you’ve got the quick‑fix tools under your belt – the three‑breath reset, the micro‑debrief, the sticky‑note reminder. Those are brilliant for the moment, but lasting resilience needs a plan that stretches beyond a single shift.

So, what does a long‑term resilience plan actually look like for a busy clinician? Think of it as a personalised roadmap that blends evidence‑based habits, organisational support, and regular reflection. It’s not a one‑size‑fits‑all checklist; it’s a living document you tweak as you gain insight into what calms your nervous system and what keeps you on edge.

1. Map your personal risk profile

Start by revisiting the Wellbeing Profile you’ve been building in the e7D‑Wellness platform. Look for patterns: Are medication‑error alerts spiking your stress scores? Do night‑shift rotations consistently push your anxiety rating higher? When you can see the data, you can set realistic targets – for example, “reduce stress spikes after night shifts by 20 % over the next two months.”

If you need a deeper dive into why these patterns matter, the article on Building Resilience: Training to Prevent Second Victim Syndrome outlines the science behind habit stacking and neuroplasticity for clinicians.

2. Build a tiered support network

Resilience isn’t a solo sport. Identify three layers of support:

Immediate peer buddy– someone you can tap for a 5‑minute check‑in after a tough case.

Mid‑term mentor or supervisor– a trusted senior who can help you debrief more formally and flag systemic issues.

Organisational resource– your hospital’s second‑victim programme, employee‑assistance line, or a dedicated wellbeing champion.

Write these names down, note their preferred contact method, and schedule a quarterly catch‑up. When the network is documented, you’re less likely to scramble for help in the heat of the moment.

3. Schedule regular “resilience reviews”

Just as you have monthly performance reviews, set a 30‑minute slot every six weeks to audit your resilience plan. Use a simple template:

Resilience Component | What I Did | Outcome / Adjustment |

Stress‑spike tracking | Logged three high‑stress events in Wellbeing Profile | Identified need for extra grounding before night‑shift handovers |

Peer‑buddy check‑ins | Met with buddy after two incidents | Found that a quick “how are you?” reduced rumination by ~35 % |

Skill refresher | Completed a simulation on medication safety | Confidence rose, error‑related anxiety dropped |

After each review, update your action items and celebrate any win, however small. Those micro‑wins add up to a stronger sense of mastery.

4. Integrate physical wellbeing into the plan

Physical health is the foundation of mental stamina. Aim for at least three movement breaks per 12‑hour shift – a 2‑minute stretch, a hallway walk, or a quick resistance‑band routine. Hydration matters too; keep a 500 ml water bottle at your bedside and sip regularly.

And don’t forget sleep. If you’re on rotating shifts, use a consistent wind‑down ritual: dim the lights, avoid screens 30 minutes before bed, and maybe try a short guided relaxation from the e7D‑Wellness app.

5. Leverage proactive health partners

Building resilience isn’t just about mental tricks; your body needs robust health support. That’s why we sometimes recommend external wellness services that complement our platform. For instance, XLR8well offers proactive health coaching that can help you optimise nutrition, manage chronic stress, and keep your immune system humming – all of which buffer the emotional fallout of second‑victim experiences.

6. Embed reflective practice

At the end of each week, spend ten minutes answering three questions in your journal:

What was my biggest stress trigger this week?

Which coping tool worked best?

What will I adjust for next week?

This habit turns episodic stress into a learning loop, making the “what is second victim syndrome” narrative less about shame and more about growth.

Does this feel like a lot? Remember, you don’t have to roll out every element at once. Pick one tier – maybe just the weekly review – and let it become automatic before adding the next layer.

By weaving data, people, and routine together, you create a long‑term resilience plan that feels like a safety net you built yourself, not a mandate from upstairs. And when the next challenging case rolls around, you’ll have a clear, practiced pathway to steady yourself, keep delivering great care, and protect your own wellbeing for the years ahead.

Step 5: Foster a Culture of Safety and Transparency

So you’ve built a toolbox of quick fixes and a weekly reflection habit – that’s huge. The next piece of the puzzle is making sure the whole team, from the night‑shift tech to the department chair, actually feels safe enough to speak up when the knot of second‑victim stress starts to tighten.

What does safety look like in a busy ward? It’s not just a poster that says “No blame.” It’s a lived experience where you can admit, “I messed up,” and get a supportive response instead of a stare‑down.

Start with a shared language

When you hear the phrase "what is second victim syndrome" in a staff meeting, pause. Does everyone know what that means, or are they nodding while thinking about something else? Take a five‑minute slot to define the term together, using plain words – no jargon. Write the definition on the whiteboard, add a quick example, and invite anyone to share a moment they’ve felt that knot. That simple act signals, “We’re all in this together.”

Ever notice how a single story can shift a whole room’s energy? That’s the power of a shared narrative.

Make reporting easy and confidential

Imagine you just realized a medication error. Your first instinct is to hide it because you’re afraid of repercussions. If the reporting process is a maze of forms and approvals, you’ll probably stay silent. Instead, champion a one‑click, confidential self‑assessment in the e7D‑Wellness platform. Clinicians can log the incident in minutes, flag their emotional state, and the system automatically routes the data to a trusted wellbeing champion – no names attached unless you choose to share.

When the barrier to reporting drops, the data starts to flow, and you can spot patterns before they become crises.

Lead with transparent debriefs

After a tough case, gather the team for a 10‑minute “what happened and what can we learn” chat. Keep the tone inquisitive, not accusatory. Start with, “What went well?” then move to, “What felt shaky?” and finish with, “One concrete tweak for next time.” Write the takeaways on a shared board so everyone sees the improvement loop in real time.

Does this feel like extra work? In reality, a 10‑minute debrief can shave hours of rumination off each clinician’s night‑shift mind.

Reward openness, not perfection

Recognition doesn’t have to be a fancy award. A quick shout‑out in the weekly email – “Kudos to Dr. Lee for raising a safety concern that led to a new checklist” – reinforces that speaking up is valued. When staff see that honesty translates into tangible change, the culture shifts from “don’t get caught” to “let’s get better together.”

Think about the last time you felt truly seen at work. That feeling sticks, right? Replicate it for your whole crew.

Build a peer‑support buddy system

Pair clinicians who work similar shifts and encourage them to check in after high‑risk procedures. A simple text like, “How are you holding up after today’s code?” can be the lifeline that prevents a second‑victim spiral. If the buddy notices prolonged silence, they can nudge the person toward the confidential self‑assessment tool.

It’s amazing how a quick “You okay?” can turn a night‑shift anxiety into a brief, productive conversation.

Measure, share, adjust

Use aggregated data from the wellbeing platform to create a quarterly safety‑culture scorecard. Show trends – maybe stress spikes drop 15 % after you introduced micro‑debriefs. Share the scorecard with the whole unit, celebrate the win, and ask, “What should we try next?”

Transparency about the numbers builds trust; it says, “We’re all accountable, and we’re all improving together.”

At the end of the day, fostering safety and transparency isn’t a one‑off project. It’s a habit, like washing your hands before every patient. By normalising the language, simplifying reporting, encouraging honest debriefs, rewarding vulnerability, and looping the whole team into the data, you create a safety net that catches you before the knot tightens.

Give one of these actions a try this week – maybe start with that five‑minute shared definition session. Notice how the conversation changes, and then keep the momentum going. Your wellbeing, and the wellbeing of everyone around you, depends on it.Step 6: Access Resources and Professional HelpAlright, you’ve spotted the knot, you’ve mapped the support landscape, and you’ve got a few quick‑fix tools in your pocket. The next logical move is to actually reach out for help – whether that’s a peer, a specialised programme, or a professional counsellor. It feels a bit like dialing a friend after a tough night shift; you know you need it, you just have to pick up the phone.First, take a breath and ask yourself: "Who can I turn to right now that I trust?" For many clinicians, the answer is a peer‑buddy who’s already familiar with the pressures of the ward. A 5‑minute check‑in after a critical incident can be a game‑changer. If you don’t have a buddy yet, set one up today. Write their name on a sticky note, add a quick “ping me after a tough case” reminder in your calendar, and make it a habit.Tap into formal second‑victim programmesMost larger hospitals now host a dedicated second‑victim support line or a scheduled debrief session. If you’re not sure whether yours does, search the intranet for “second‑victim” or ask your quality‑improvement office. When you find the programme, grab the contact details and save them in your phone – treat it like an emergency contact for your own wellbeing.When you call, you’ll often be routed to a trained peer supporter or a mental‑health professional who understands the clinical context. These people are equipped to help you process the event without judgment, and they can guide you toward further resources if needed.Leverage the e7D‑Wellness platformPlatforms like e7D‑Wellness make the whole process feel less intimidating. After a stressful incident, log a quick entry in the confidential self‑assessment. The system tags your emotional state and automatically suggests the nearest support option – whether that’s a peer‑buddy call, a scheduled debrief, or a referral to a counsellor.Because the data is anonymised, you can also see trends across your team. If several clinicians are logging high‑stress spikes after a particular procedure, you have concrete evidence to bring to leadership and push for system‑level fixes.Professional mental‑health servicesSometimes the conversation with a peer isn’t enough. If you notice persistent rumination, sleep disruption, or physical symptoms (headaches, stomach knots) for more than a week, consider a professional therapist. Many institutions offer Employee Assistance Programs (EAP) that provide a limited number of free counselling sessions.When you contact the EAP, be clear about the context – “I’m a surgeon who just experienced a near‑miss and I’m feeling stuck.” Most counsellors have experience with healthcare‑related trauma and can tailor techniques like cognitive‑behavioural therapy or mindfulness to your shift schedule.Specialty resources for specific rolesNurses, med‑techs, and EMS staff often have role‑specific support groups. For example, some hospitals run a monthly “Night‑Shift Survivors” round‑table where you can share stories, swap coping hacks, and even co‑author a quick‑reference checklist for the next shift. These groups not only reduce isolation but also create a repository of practical solutions that you can pull from the next time you’re on call.If you’re a medical student or resident, your training programme likely has a wellness officer. Reach out early – they can connect you with mentorship, simulation‑based error‑learning labs, and even grant you time off to recover.External resources you can browse on your own timeBeyond the hospital’s built‑in services, there are reputable online toolkits that compile evidence‑based strategies for second‑victim recovery. A quick Google search for “medical errors and the rise of second victims” will surface a solid overview that can help you articulate your experience when you speak with leadership.Here’s a handy checklist you can print and keep in your locker:Identify the incident and date.Note your immediate emotional and physical reactions.Contact your peer‑buddy (or set a reminder to do so).Log the event in e7D‑Wellness within 30 minutes.If symptoms persist >7 days, call the EAP or a licensed therapist.Follow up with your manager to discuss systemic improvements.By following these steps, you turn a vague feeling of overwhelm into a concrete action plan. The knot won’t untie itself, but each of these moves loosens it a little more.Remember, seeking help isn’t a sign of weakness – it’s the same mindset you bring to a patient when you order a test because you suspect something deeper. You deserve that same level of care.And if you’re wondering how all of this ties back to the bigger picture of why second‑victim syndrome matters, take a look at this article on Medical Errors and the Rise of Second Victims . It frames the whole conversation around system‑level safety, which makes your personal advocacy even more powerful.FAQWhat is second victim syndrome and why does it matter?Second victim syndrome describes the emotional fallout clinicians experience after a medical error or adverse event. It’s not just a fleeting feeling of guilt – it can manifest as anxiety, insomnia, or even physical symptoms that linger for weeks. Understanding what is second victim syndrome matters because untreated distress can erode confidence, affect patient safety, and increase burnout risk for doctors, nurses, and allied staff.How do I know if I’m a second victim?Look for a cluster of signs: replaying the incident in your mind, feeling a knot in your stomach, racing thoughts, or an urge to avoid similar cases. If you notice these symptoms within 24‑48 hours and they persist beyond a few days, you’re likely in the second‑victim zone. A quick self‑check is to write down what you’re feeling and see if more than half of the entries are self‑critical or fear‑based.What should I do immediately after a triggering event?First, pause and take three deep breaths – inhale for four counts, hold two, exhale for six. Then, ground yourself with the five‑sense technique (name what you see, hear, touch, smell, taste). Finally, jot a brief note in a confidential journal or the e7D‑Wellness self‑assessment tool, tagging the incident and your emotional state. This trio of breath, grounding, and documentation turns raw emotion into actionable data.Can peer support really help, or is it just “talking it out”?Peer support works because it normalises the experience and provides a safe space for shared language. A five‑minute micro‑debrief with a trusted colleague can reduce rumination by up to 35 % according to recent wellbeing studies. The key is to keep it factual and brief: describe what happened, acknowledge how you feel, and identify one small tweak for the next similar case.When should I seek professional help instead of relying on peers?If symptoms like sleeplessness, headaches, or persistent anxiety linger longer than a week, or if you notice a drop in clinical performance, it’s time to reach out to a mental‑health professional. Many hospitals offer Employee Assistance Programs (EAP) that provide confidential counselling. Be clear about the context – “I’m a surgeon dealing with a near‑miss and can’t shake the anxiety” – so the therapist can tailor techniques to the fast‑paced healthcare environment.How does the e7D‑Wellness platform fit into my recovery plan?e7D‑Wellness lets you log stress spikes instantly, tag them with the coping strategy you used, and view trends over time. By seeing which tools – like breathing or micro‑debriefs – consistently lower your scores, you can build a personalised “fast‑track” playbook. The platform also anonymises data, so you can share aggregate insights with leadership without exposing individual identities.What long‑term steps can I take to prevent second‑victim burnout?Start by mapping a tiered support network: a peer buddy for quick check‑ins, a mentor for deeper debriefs, and organisational resources such as a second‑victim support line. Schedule a quarterly resilience review where you audit your stress logs, adjust coping tactics, and celebrate small wins. Integrate physical habits – regular movement breaks, hydration, and consistent sleep rituals – because a strong body underpins emotional resilience.ConclusionWe've walked through the tangled feelings that surface when a medical error hits, and you now have a clearer picture of what is second victim syndrome.Remember the moment we started: the knot in your stomach, the replay loop, the urge to disappear. You’ve seen how quick‑fix tools, a tiered support network, and data‑driven tracking can untie that knot.So, what’s the next move? First, log any stress spike in your e7D‑Wellness self‑assessment. Then, reach out to a peer buddy within the hour. Finally, schedule a brief review of your wellbeing data each month – it turns raw emotion into actionable insight.Imagine looking back in a few months and seeing a steady dip in anxiety scores. That’s the power of turning awareness into habit.It’s easy to let the silence linger, but you don’t have to go it alone. Use the resources you’ve gathered, lean on the platform, and keep the conversation alive with your team.Ready to take the first step? Grab your notebook, note today’s biggest takeaway, and set a reminder to log it tonight. Your wellbeing journey starts now.And don’t forget – resilience is a marathon, not a sprint. Celebrate each small win, revisit your plan quarterly, and watch how the cumulative effect reshapes your confidence and patient care.

Comments